Homoiconicity isn’t the point

I’ve never really understood what “homoiconic” is supposed to mean. People often say something like “the syntax uses one of the language’s basic data structures.” That’s a category error: syntax is not a data structure, it’s just a representation of data as text. Or you hear “the syntax of the language is the same as the syntax of its data structures.” But S-expressions don’t “belong” to Lisp; there’s no reason why Perl or Haskell or JavaScript couldn’t have S-expression libraries. And every parser generates a data structure, so if you have a Python parser in Python, then is Python homoiconic? Is JavaScript?

Maybe there’s a more precise way to define homoiconicity, but frankly I think it misses the point. What makes Lisp’s syntax powerful is not the fact that it can be represented as a data structure, it’s that it’s possible to read it without </em>parsing</em>.

Wait, what?

It’s hard to explain these concepts with traditional terminology, because the distinction between reading and parsing simply doesn’t exist for languages without macros.

Parsing vs reading: the compiler’s view

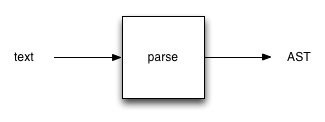

In almost every non-Lispy language ever, the front end of every interpreter and compiler looks pretty much the same:

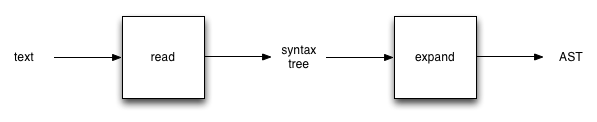

Take the text, run it through a parser, and you get out an AST. But that’s not how it works when you have macros. You simply can’t produce an AST without expanding macros first. So the front-end of a Lispy language usually looks more like:

What’s this intermediate syntax tree? It’s an almost entirely superficial understanding of your program: it basically does paren-matching to create a tree representing the surface nesting structure of the text. This is nowhere near an AST, but it’s just enough for the macro expansion system to do its job.

Parsing vs reading: the macro expander’s view

If you see this statement in the middle of a JavaScript program:

for (let key in obj) {

print(key);

}

you know for sure that it’s a ForInStatement, as defined by the spec (I’m using let because… ES6, that’s why). If you know the grammar of JavaScript, you know the entire structure of the statement. But in Scheme, we could implement for as a macro. When the macro expander encounters:

(for (key obj)

(print key))

it knows nothing about the contents of the expression. All it knows is the macro definition of for. But that’s all it needs to know! The expander just takes the two subtrees, (key obj) and (print key), and passes them as arguments to the for macro.

Parsing vs reading: the macro’s view

Here’s a simple for macro, written in Racket:

(define-syntax-rule (for (x e1) e2)

(for-each (λ (x) e2) e1))

This macro works by pattern matching: it expects two sub-trees, the first of which can itself be broken down into two identifier nodes x and e1, and it expands into the for-each expression. So when the expander calls the macro with the above example, the result of expansion is:

(for-each (λ (key) (print key)) obj)

The power of the parenthesis

If you’ve ever wondered why Lisp weirdos are so inexplicably attached to their parentheses, this is what it’s all about. Parentheses make it unambiguous for the expander to understand what the arguments to a macro are, because it’s always clear where the arguments begin and end. It knows this without needing to understand anything about what the macro definition is going to do. Imagine trying to define a macro expander for a language with syntax like JavaScript’s. What should the expander do when it sees:

quux (mumble, flarg) [1, 2, 3] { foo: 3 } grunch /wibble/i

How many arguments does quux take? Is the curly-braced argument a block statement or an object literal? Is the thing at the end an arithmetic expression or a regular expression literal? These are all questions that can’t be answered in JavaScript without knowing your parsing context — and macros obscure the parsing context.

None of this is to say that it’s impossible to design a macro system for languages with non-Lispy syntax. My point is just that the power of Lisp’s (Scheme’s, Racket’s, Clojure’s, …) macros comes not from being somehow tied to a central data structure of the language, but rather to the expander’s ability to break up a macro call into its separate arguments and then let the macro do all the work of parsing those arguments. In other words, homoiconicity isn’t the point, read is.